Anaemia has been acknowledged as a frequent systemic complication and/or extraintestinal manifestation in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)1 with iron deficiency (ID) being the primary cause of disease2 with an estimated prevalence of iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) among patients with IBD at approximately 45 %.3

Considering the potential effect on hospitalization rates and consequences for patients quality of life, anaemia has been described as a significant and costly complication of IBD.4 However, ID and IDA are under-treated.5

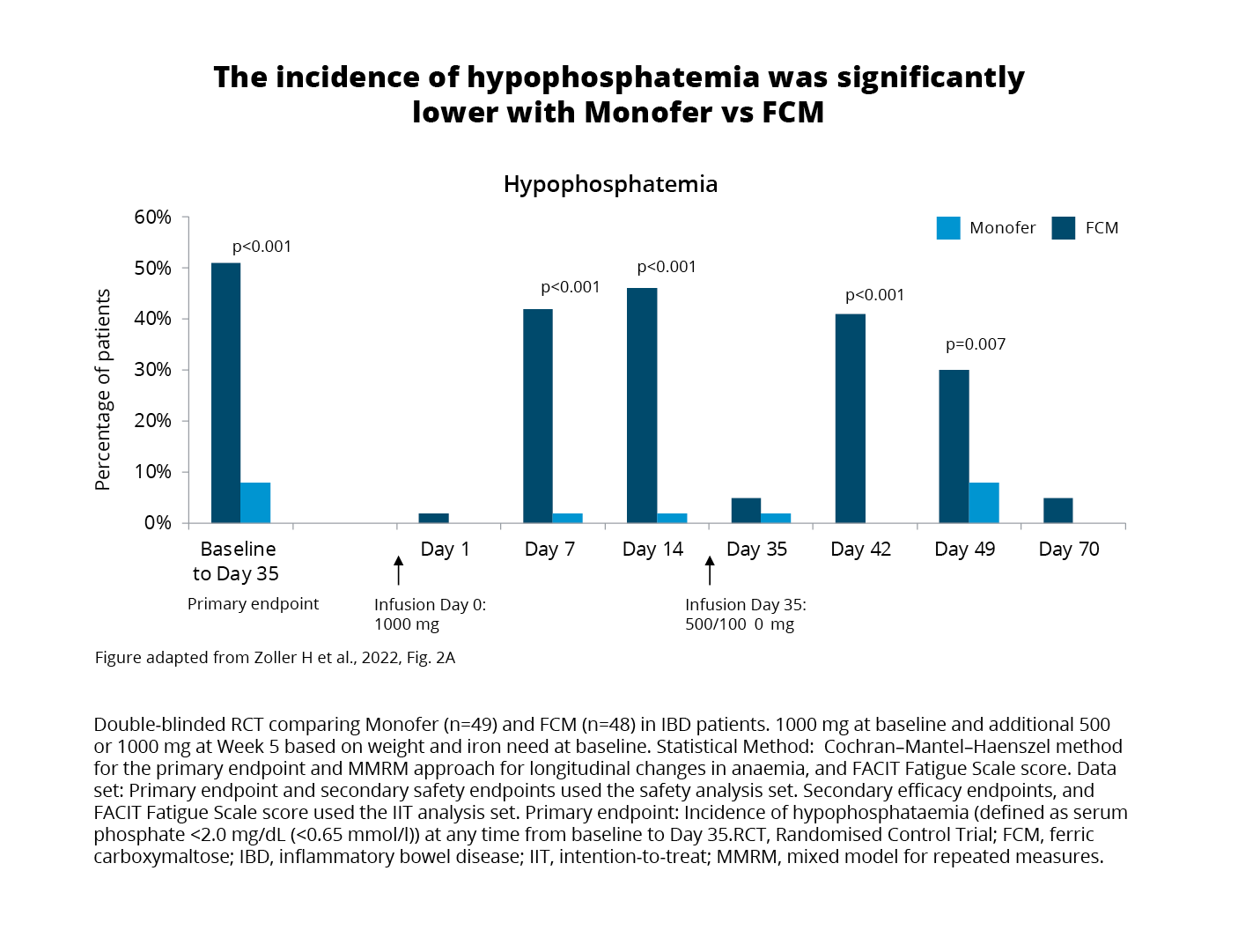

The PHOSPHARE-IBD study is the first randomized double-blind clinical trial to compare the incidence of hypophosphataemia after treating inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients diagnosed with Iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) with intravenous irons; FCM1 or FDI2,3 The results substantiate previous findings showing that patients assigned to receive FCM1 had a significantly higher incidence of hypophosphataemia compared to certain other iv iron compounds.4–6

Even when IBD patients are screened, ID and IDA might be overlooked as commonly used laboratory tests may be compromised due to several pathophysiological mechanisms related to the inflammatory nature of IBD9

Consequently, when evaluating ID and IDA in IBD the following mechanisms should be taken into consideration:

Hemoglobin: Iron deficiency should not be excluded despite normal Hb as Hb levels do not decline until a significant amount of iron is lost.10

Ferritin: Besides binding and storing iron in the liver, spleen, and reticuloendothelial system ferritin is also an acute-phase protein and can be increased in the presence of inflammation.11 Following, the interpretation of serum ferritin in patients with inflammation is tricky.5

Hepcidin and ferroportin: The hepatic peptide hormone hepcidin functions as an important regulator of iron homeostasis by controlling ferroportin – the sole iron exporter. However, hepcidin also increases as a response to inflammation.13 The increased levels of hepcidin caused by inflammation will promote the degradation of ferroportin and subsequently impair the exportation of cellular iron into plasma.13

Transferrin saturation: The main iron carrier protein is transferrin.6 In the presence of inflammation, a normal ferritin level does not exclude ID.14 In this case, testing TSAT provides an indication of the extent of iron utilization.10

Soluble transferrin saturation receptor: The TSAT level only indicates the extent of iron utilization.4 A more extensive workup should include soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR) testing.8 sTfR is a truncated form of the cellular transferrin receptor and circulates bound to transferrin.10 It is released in proportion to the expansion of erythropoiesis in the bone marrow and is not regulated by inflammation.5 As a reflector of erythropoiesis, sTfR correlates with the amount of iron available.

Hypophosphatemia is characterized by low levels of phosphate in the blood. The divergence between FCM1 and FDI2 arises due to FCM1 and FDI2’s different effects on fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) affecting phosphate regulation.3 This occurs through the stimulation of renal phosphate excretion and downstream effects on 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D and parathyroid hormone (PTH) that maintain hypophosphataemia.3

Symptoms of hypophosphataemia can be mild and are relatively non-specific, such as fatigue, which makes them challenging to differentiate from similar symptoms associated with IDA and IBD.7 However, the consequences of hypophosphatemia can extend beyond low phosphate levels with reports of complications such as severe muscle weakness and alterations in mineral and bone metabolism that can result in osteomalacia and fractures.8

The PHOSPHARE-IBD trial was conducted at 20 outpatient hospital clinics in Europe with a scope to explore the following endpoints:3

Adults with IBD and IDA (haemoglobin (Hb) <130 g/L and serum ferritin ≤100 μg/L ) were randomized 1:1 to receive either FCM1 or FDI2 treatment.3 A total of 156 patients were screened and 97 (48 FDI2, 49 FCM1) were included to receive either one dose of FCM1 or FDI2 using identical haemoglobin- and weight-based dosing regimens at baseline and at Day 35.3

Exploring the primary endpoint using the safety analysis set (all patients who received at least one dose of the study drug) revealed comparable effects on haemoglobin (Hb) and iron stores after receiving either FCM1 or FDI2.3 On the contrary, hypophosphatemia (serum phosphate <2.0 mg/ dL (<0.65 mmol/l)) occurred in:3

(Figure 1)

When compared with FDI2, FCM1 treatment was associated with more pronounced changes in biomarkers showing increases in intact FGF23 and renal phosphate excretion, and PTH, and decreases in 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D all related to an increased risk of hypophosphatemia.3

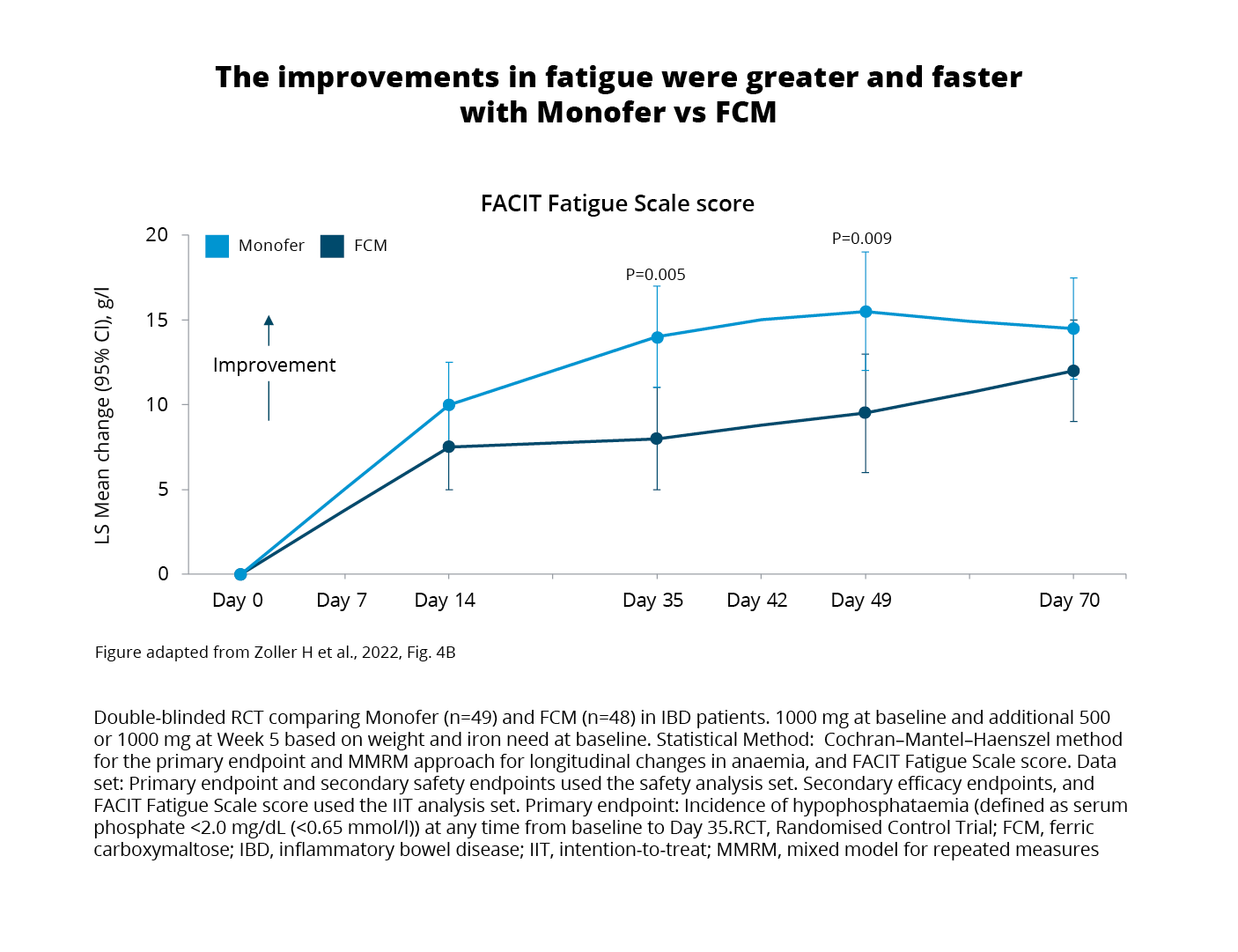

Analysis of patient-reported fatigue scores using the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) Fatigue Scale was carried out within the intention-to-treat (ITT) population.3 The analysis aimed to explore the hypothesis of a potential relationship between phosphate level and fatigue.3 Results showed improved scores in both treatment groups. However, it is noteworthy that:

Despite recovering from hypophosphataemia following their initial treatment, patients treated with FCM1 still experienced prolonged biochemical changes linked to elevated FGF expression.3 Specifically, bone-specific ALP remained elevated on Day 70 and beyond implying a sustained impact on bone turnover.3

Based on the study design the results from the PHOSPHARE-IBD trial indicate that differences in hypophosphataemia are not a class or dose effect of IV iron or due to dosing, schedule, or patient factors but solely an adverse effect of FCM1 driven by increases in FGF23.3

Furthermore, the discovery of significant differences in patient-reported fatigue and the link to hypophosphataemia severity offers valuable insights that advance the field.3 This information could assist in guiding future treatments by informing clinicians and patients about the short-term effects of hypophosphataemia on quality of life and the risk of long-term effects on mineral and bone metabolism increasing the risk of osteomalacia and fractures.3

Disclaimer

Despite the dramatically different effects on plasma phosphate homeostasis, FDI2 and FCM1 treatment have both been consistently shown to improve quality of life in patients with iron deficiency. The present trial confirms that both formulations effectively corrected IDA, as evidenced by almost identical Hb responses leading to a rise of 20–30 g/L in both groups as well as correction of serum iron parameters.3

ATC: B03AC. Trevärt järn, parenteralt preparat. Injektions-/infusionsvätska 100 mg/ml. Injektionsflaska i förpackningsstorlekar: 1x5 ml, 1x10 ml, 5x1 ml, 5x5 ml och 2x10 ml.

För fullständig information och priser, se www.fass.se.

Indikation: Monofer är indicerat för behandling av järnbrist vid följande tillstånd: När perorala järnpreparat är ineffektiva eller inte kan användas. Vid kliniskt behov av snabb tillförsel av järn. Diagnosen järnbrist måste baseras på tillämpliga laboratorieprover. Kontraindikationer: Anemi som inte orsakas av järnbrist. Järnöverbelastning eller rubbning i kroppens användning av järn. Överkänslighet mot den aktiva substansen Monofer eller mot något hjälpämne. Konstaterad allvarlig överkänslighet mot andra parenterala järnprodukter. Dekompenserad leversjukdom. Särskilda varningar och försiktighetsmått: Parenteralt administrerade järnpreparat kan ge upphov till överkänslighetsreaktioner inklusive allvarliga och potentiellt dödliga anafylaktiska/anafylaktoida reaktioner. Överkänslighetsreaktioner har även rapporterats när tidigare doser av parenterala järnkomplex inte har resulterat i några oönskade effekter. Det har förekommit rapporter om överkänslighetsreaktioner som har utvecklats till Kounis syndrom. Risken är större för patienter med konstaterade allergier inklusive läkemedelsallergier, däribland patienter med svår astma, eksem eller andra atopiska allergier i anamnesen. Det finns även en ökad risk för överkänslighetsreaktioner mot parenterala järnkomplex hos patienter med immunologiska eller inflammatoriska tillstånd. Monofer ska endast administreras när personal som är utbildad i att bedöma och hantera anafylaktiska reaktioner finns tillhands, i en miljö där lokaler och utrustning för återupplivning garanterat finns tillgängliga. Varje patient ska observeras avseende biverkningar under minst 30 minuter efter varje injektion av Monofer. Om överkänslighetsreaktioner eller tecken på intolerans uppkommer under administrering måste behandlingen stoppas omedelbart. Lokaler för hjärt-lungräddning och utrustning för hantering av akuta anafylaktiska/anafylaktoida reaktioner ska finnas tillgängliga, inklusive en injicerbar 1:1 000 adrenalinlösning. Ytterligare behandling med antihistaminer och/eller kortikosteroider ges efter behov. Hos patienter med kompenserad leverdysfunktion ska parenteralt järn endast administreras efter noggrann nytta/riskbedömning. Administrering av parenteralt järn ska undvikas hos patienter med leverdysfunktion där järnöverskott är en förvärrande faktor, särskilt vid porfyria cutanea tarda (PCT). Noggrann övervakning av järnstatus rekommenderas för att undvika järnöverskott. Parenteralt järn bör användas med försiktighet vid fall av akut eller kronisk infektion. Monofer bör inte användas för patienter med pågående bakteriemi. Hypotensiva reaktioner kan uppträda om den intravenösa injektionen ges för snabbt. Försiktighet bör vidtas för att undvika paravenöst läckage vid administrering av Monofer. Paravenöst läckage av Monofer kan leda till hudirritation och eventuellt långvarig brun missfärgning vid injektionsstället. Vid paravenöst läckage måste administreringen av Monofer stoppas omedelbart. Graviditet: Det finns endast begränsade data från användning av Monofer hos gravida kvinnor. En noggrann nytta/risk-bedömning krävs därför före användning under graviditet. Fosterbradykardi kan förekomma efter administrering av parenteralt järn. Tillståndet är vanligtvis övergående och är en följd av en överkänslighetsreaktion hos modern. Amning: Vid terapeutiska doser av Monofer förväntas inga effekter hos det ammade barnet. Produktresumé uppdaterad 2022-08-11

Pharmacosmos A/S

Roervangsvej 30

DK-4300 Holbaek, Danmark.

07-SCAN-11-09-2023.v1

PHOSPHARE-IBD study presentation

Gastro advertorial Sweden

Cardio advertorial Sweden

Gastroenterology article 1